‘We did not even know we were happy’: Interview with Yurii Matviienko on the life of the community where the border became a front line

Life in the border community before the war seemed normal: school, hospital, roads, work, sports, plans for development. What was perceived as everyday life was in fact a fragile balance of peace, human labour and faith in tomorrow. ‘We did not even know we were happy,’ says Yurii Matviienko, Head of Shalyhyne community. And in this statement, there is no nostalgia, only a sober realisation of how quickly the things we take for granted can disappear.

Full-scale war transformed everyday life: the border became a front line, some villages were abandoned, infrastructure was destroyed, and the economy ground to a halt. Instead of making usual management decisions, the focus shifted to evacuation, safety, and preserving human life. Along with these losses came a clear understanding of the value of peace, of having people on the land, of having functioning schools and hospitals, and of having stable business rules.

The history of the Shalyhyne community is not just about resilience on the front line. It is also about the extent to which the state recognises border areas not as the periphery, but as an area of responsibility. It is not just about rebuilding destroyed infrastructure. It is also about preserving human, economic and institutional life where the state border lies.

By Dmytro Syniak

Shalyhyne is located on both banks of the Lapuha River, 20 kilometres from Hlukhiv and 10 kilometres from the road that used to connect Hlukhiv to Kursk. The settlement is surrounded by the dense forests of the Polissia region, home to birch, pine and oak trees… In the second half of the 19th century, the renowned Tereshchenko family, who were sugar industrialists and patrons of the arts, ruled here. They made significant renovations to the local infrastructure and even built a hospital in Shalyhyne. Given this history of responsible stewardship, perhaps it is no surprise that the Shalyhyne community was one of the first to amalgamate in 2016.

The community covered an extensive area of 257.5 square kilometres, yet it had a sparse population of just over 4,000 people, with 3,000 residing in the community central locality. While the average population density in Ukraine was 67–68 people per square kilometre, this figure was only 16 in the Shalyhyne community. Another distinctive feature of the community was that it shared a 46 km border with russia. This border is now a front line, with deadly drones, shells, and missiles flying in all the time from behind it. Consequently, the population has declined further still, now numbering only a few hundred, mostly of retirement or pre-retirement age.

Yurii Matviienko, Mayor of Shalyhyne, sounds both profoundly fatigued and determined to persevere until the end, regardless of the consequences. He is reluctant to answer questions and refuses to disclose any figures, localities or even regions. Four years of war, during which the community has worked closely with the military, have taught him to be cautious with information that could potentially be advantageous to the enemy.

Yurii Matviienko, Head of Shalyhyne community

‘Before the war, we never even thought about how good our lives were!’

What losses has Shalyhyne community suffered as a result of the full-scale russian invasion?

To be honest, I feel that God was watching over us because our losses could have been much greater. In 2022, we evacuated people under fire: elderly residents were carried on stretchers and transported by boat across the Klevan River. At that time, all the bridges across the river had already been blown up. Nine of our residents died during the full-scale war. Among them were a teacher and a social worker. A russian shell exploded in front of the social worker’s bicycle as she was riding to visit her clients. My deputy was also killed by a mine while conducting an evacuation. One of our utility workers hit a mine while working. Thankfully, he survived, but the utility vehicle he was using was destroyed. Two of our residents died due to their own recklessness after coming into contact with unexploded russian drones.

Did you find it difficult to manage such a vast territory with such a small population?

No, because despite the large area, all our villages were located close to each other quite compactly. The fact that we amalgamated earlier than other communities gave us a considerable competitive advantage. We entered 2022 feeling confident.

What was Shalyhyne community like before the war?

Before the war, we never thought about how good our lives were. Now, we sometimes get together with colleagues and reminisce… We never realised how happy we were back then. The community was growing, and we were buying new equipment and carrying out major repairs everywhere. Although our budget was small and there were not many people, there was enough for everything. We planned large projects involving partners and the state – primarily the construction and repair of roads. We had amateur arts groups, libraries, schools, and kindergartens. We even had our own hospital, which also housed a general practice clinic. All our villages had water supply systems that we were actively renovating, and the four largest villages had gas supply systems. Public transport worked as people needed it to, and no one complained about transport connections. And what sports we had! Despite having only 4,000 residents, we had three football teams and three volleyball teams! One of our football teams even played in the regional championship. The russians destroyed, burned and ruined all of this!

What have the years of war taught you? In what ways are you different from your pre-war self?

They taught me to treat people more carefully. Whereas before we only sought to provide a better service, now we are trying to save the lives of the local population. We understand that if people have chosen to remain in dangerous villages during the autumn, they will not leave until spring. This means we have to provide them with not only food, but also firewood, generators, fuel, and anything else they might need. We are trying to do this as much as possible. This was not the case before. The main focus of our work is now to save human lives, although unfortunately people often do not realise this. Sometimes we want to save and protect them more than they want to save and protect themselves.

Evacuation of residents from Shalyhyne across the Klevan River in spring 2025

A general practice family medicine clinic in Shalyhyne, which served 2,100 people. Russian drones deliberately destroyed it between 26 and 28 April 2025

Destroyed vehicle belonging to utility company of Shalyhyne community

Founded in 1968, the school in Shalyhyne was damaged by russian guided missiles in 2024. The following year, it was completely destroyed by russian drones. Fortunately, although school staff were present at the time of the strikes, they were unharmed

How to manage a community in extreme conditions

The Shalyhyne Settlement Council continues to hold sessions and make decisions, even though most residents have been evacuated and others are under fire almost daily. How do you manage to convene local councillors and maintain the administration in such terrible conditions?

Most of the councillors are on site in Shalyhyne… It seems that two or three have left, but modern communication technologies mean this is not a problem. We have a fairly cohesive and responsible group of councillors: in nine years of work, there has only been one instance where there was no quorum. Naturally, we also have an opposition that is personally opposed to me. However, this opposition comprises only two or three people, and their different opinions make our meetings and sessions more democratic. For the most part, the settlement council comprises reasonable people who understand the current situation we all find ourselves in because of the war and the border with russia.

In your opinion, where is the line between the responsibilities of an administrator, who is primarily responsible for the budget and procurement, and those of a crisis manager, whose duties primarily include evacuations, providing humanitarian aid, and meeting the needs of residents in villages that are almost cut off from the world..?

There is no such line. One day you are an administrator, the next you are a crisis manager – it has always been that way. Before the full-scale invasion, the challenges were simply not that global. If there was a pipe rupture or another accident, for example, your role would immediately change from administrator to crisis manager. The same thing is happening now, only instead of pipe accidents, we have shelling, deaths, and injuries. I suppose you could say that the role of crisis manager is in greater demand now than before the full-scale invasion.

How does the community help the army while maintaining a civilian authority?

It provides significant support, not only through its own budget, but in other ways too. I will not reveal any more information on this.

Does the community feel the attention of the regional authorities? Do you feel that you have been left to fend for yourselves?

Not at all! Quite the contrary! Since we lost all our local business, we have survived solely on state subsidies. Some funds come through the district and regional authorities, with whom we work closely. In fact, each of our households that met certain criteria received UAH 19,000 from the state to help them prepare for winter. However, some residents spent these funds on other purchases and then came to us begging for help. But these are exceptions rather than the rule.

What is the most difficult part of your job right now?

Working with people who have remained in evacuation zones. Some residents of several villages closer to the border refuse to leave. We are compelled to perform certain tasks there based on our capabilities and the security situation. We are willing to fulfil the residents’ wishes only on the condition that the lives and health of those carrying out these wishes are preserved. The primary task in any field is now to preserve the lives of Ukrainians: those who are fighting, those who are working, and those who are no longer able to work. Besides, we are currently unable to provide all services to people. For example, the staff at our hospital have been completely relocated after the russians destroyed its premises. Therefore, if any residents of border villages need medical assistance, this poses a serious challenge for us.

School in Shalyhyne after a fire caused by russian missile strikes

Everything that remained of the school gym

Life in the burned-out land zone

How do you deal with the situation?

With the help of social workers. We have increased their number, provided them with transport, and significantly raised their salaries. This is because their work is very dangerous. Utility workers also received a pay rise, and despite the snowy winter, all the roads to our villages where people still live were cleared of snow.

Do you also have to clear the roads of mines and ammunition?

Yes, sometimes, and we involve the military in this. However, the russians left us with so many of these ‘gifts’ and dropped so many from drones and artillery that we will not be able to get rid of them any time soon, even after the war.

What do residents who refuse to leave need most right now? Food, building materials for quick repairs, means of communication?..

What people need most is for the russians to be pushed back from the border, for them to stop shelling the community, for their guns not to reach us. For them to leave us alone. We have enough food and generators, and so on. We would be very grateful if someone could give us an evacuation vehicle. Our car, a nearly new Mercedes with only 15,000 km on the clock, was burned down by half a dozen russian drones last year. Miraculously, the driver was unharmed. What remains of this wonderful car is a sad reminder of our inhuman enemy and the fact that civilians – women, children and pensioners – and their lives mean nothing to the russians.

Why are people not leaving dangerous villages?

Because they do not fully realise the danger. They also do not realise that, at some point, we may refuse to deliver certain items in order to avoid risking the lives of our colleagues. They think that this somewhat distorted situation, in which we provide them with everything they need, will last a long time, if not forever. People also do not want to leave the family homes and property they have accumulated over years or even decades. However, when russian shells and drones destroy their property, their view of the situation changes. But as long as their property is intact, people try to believe in the best outcome. Such is human nature.

But in border villages, there is probably no electricity, gas or communication. How do people live there? Like in the Middle Ages?

It depends on the individual. Some people sit by candlelight in the dark at night, fetch water from the well, and live off their own garden produce. Others have set up a protective shelter in their basement, where they eat and sleep. Not just for a month or two, but for over a year. However, we are doing everything we can to ensure that all our residents have access to our services. I should also mention that six of our ten villages are completely deserted, which makes our job somewhat easier. These villages are currently inaccessible as all roads are blocked by the military.

How can administrative services be provided in the surviving villages? It is dangerous now. Previously, people could visit the Administrative Services Centre to obtain a certificate. What is the situation now?

It is the same now, except that we have decentralised the Administrative Services Centre. Most of its functions have been taken over by starostas, who are trying to make people’s lives as easy as possible. If the starosta cannot help, people go to the settlement council. We have relocated it not too far from Shalyhyne, and all issues are resolved there. We also actively use cloud services, which means information can be accessed from anywhere in the world.

Is there a plan to preserve the remaining infrastructure until better times?

What plan are you talking about? We have preserved what the enemy did not destroy. However, this does not guarantee that these facilities will survive until better times. The enemy can destroy them at any time – even just for fun. Unfortunately, we do not have access to many of the destroyed facilities, so we cannot evaluate the extent of the damage. We managed to remove some property from these facilities, but not all of it, so unfortunately it is probably buried under the rubble. Incidentally, the vast majority of our infrastructure was destroyed last year. Before Sudzha, the situation was still bearable.

One of the schools in Shalyhyne community looks like this (photo on the left). Destroyed private house in Shalyhyne (photo on the right)

‘Shoulder-to-Shoulder’ with the whole of Ukraine

How do you keep in touch with community residents? With both those who stayed and those who left?

From the moment the full-scale war began, the task of finding out where people were and where they had gone fell to every starosta district. Literally everyone. Most of our residents went to stay with their children or other relatives, while some bought new homes and some are renting. Many of them have already received certificates under the eVidnovlennya programme and have settled into their new homes. I must say that our people are quite patriotic. This is why few people have resigned since the full-scale invasion. Personally, I live five kilometres from the border and rarely leave this place. Yes, unfortunately, sometimes there is no electricity or internet. But I want to stay with my people and oversee the work of our structural unit employees, such as electricians and utility workers, from here...

What kind of assistance do your people who have become internally displaced persons receive?

Every person who agrees to be evacuated receives UAH 5,000 from our budget. Last year, approximately UAH 7 million was spent on this item of expenditure, and UAH 10 million is expected to be spent in 2026. This means that everyone who left the community received this money. For most of our residents, this is a significant sum. As far as I know, no other community in Sumy region has such a programme. We also provide assistance for childbirth, the treatment of cancer patients and injured residents, repairing damage to real estate, helping families with children prepare for the educational process, supporting community residents who have been called up for military service, treating injuries sustained by those called up for military service, and burying civilians and community residents who have died.

Do you have any partnerships with municipalities in the European Union? Do any international humanitarian organisations support your community?

We work with these organisations through the regional administration. With regard to partnerships with EU municipalities, we have close ties with the German town of Winzer. Our children have already visited Winzer on holiday, and we now want to expand our cooperation with the town. We are currently in talks about this.

Does your community participate in the ‘Shoulder-to-Shoulder: Cohesive Communities’ project? If so, how do your partner communities support you?

Yes, we have memoranda of cooperation with two communities on this project, with which we are working quite successfully. However, I will not disclose the nature of the assistance they provide. I can say, however, that one of our partner communities organised a ten-day holiday for our children in the Czech Republic and Germany. It was extremely important for the children to escape, even if only temporarily, from our reality, where explosions and air raid sirens are a daily occurrence. This community also provided us with several generators. Another partner community gave us a fire engine, which we value as highly as gold. Their representatives came and took those of our pensioners who agreed to move into a nursing home. We sent our social worker with them to ensure that these pensioners had everything they needed. I will not name our partners in case russian missiles are fired at them because of what I have said. If this is important to you, please contact the Regional Military Administration.

Then tell me, what kind of support from the partners in the ‘Shoulder-to-Shoulder’ project do you need most? Or what kind of support do you value most?

No matter how much I talk about material things, they are not the most important thing. What matters most is that, thanks to this wonderful project, we really feel supported by our partner communities. Their moral support means so much to us. When they call us and simply ask what we need, it is extremely inspiring. At such moments, we realise that, even though they are far away in western Ukraine, people remember us and care about us – not government officials, but people just like us. This is very valuable to us.

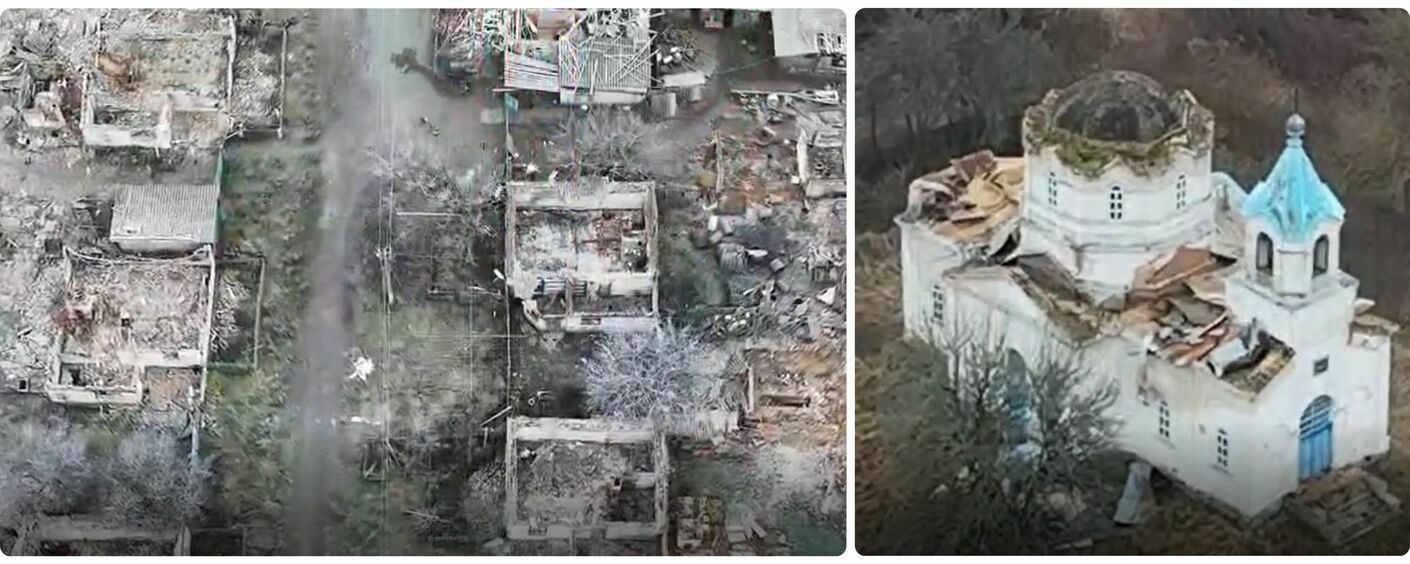

Remains of the water tower in Shalyhyne (photo on the left). All border villages in Shalyhyne community look like this (photo on the right)

Economy under fire

At a public event recently, you discussed tax relief for farmers in 2026. How can farmers be persuaded not to leave dangerous areas for good? Is it even possible to continue farming in your community?

There is no such possibility because our entire community is located within ten kilometres of the border. Working in this zone is very risky. In fact, we have no businesses left. One farmer is still somehow managing to work, but I do not know how long he will last. We could, of course, persuade him and offer him all kinds of benefits and subsidies, but what if he agrees and it causes him or his employees harm? What if, God forbid, one of them dies? Safety is much more important to us than the taxes that entrepreneurs could potentially pay us. We have been offering tax relief to farmers since 2023. A special commission studied each entrepreneur’s situation and, if necessary, exempted them from land tax or rent payments. I think we managed to hold out until last year purely because of this.

Since power grids have become a priority target for the russians, are you using any unconventional solutions to keep the lights on for those who have remained in the community? Have generators and solar panels become the only option for critical facilities?

But so far, these are probably the only solutions that can hardly be called unconventional, given how widespread they are. As I mentioned, one of our partner communities in the ‘Shoulder-to-Shoulder’ project helped us with generators. We gave some of these generators to people and are keeping others in reserve in case of further electricity problems. Solar panels did not work out for us. We had some ideas and projects, but unfortunately the war prevented us from starting work on them. Unfortunately. We are also taking a traditional approach, restoring what the enemy has damaged. During the restoration process, we are also trying to provide additional protection for all important facilities.

Communities such as yours face extraordinary conditions and probably require exceptional legislation, norms and rules. Do you think the current regulatory framework is sufficient? What changes to legislation do you expect from the state?

During the full-scale war, I heard many interesting ideas from officials at various levels. In particular, the President announced plans to develop mechanisms for granting three-year incentives to communities such as ours. These incentives would include a significant salary increase for those who agree to live and work in the border area. There was also talk of a special approach to work experience: one year of work in the border area would count as two years. For now, we are retaining staff with high salaries, which we have increased at the expense of our own budget. Those who risk their lives and health by travelling to dangerous villages should be paid more than their office-based peers.

At its last session on 26 January, the Shalyhyne Settlement Council approved the 2025 budget implementation report. According to the report, the community’s revenues totalled UAH 60.7 million, while expenditure reached UAH 48.5 million. The remaining funds were transferred to the current year. Revenues for this year are planned at UAH 47.7 million and expenditures at UAH 55.4 million. According to the Head of Shalyhyne community, the main budget items are defence and social programmes. There are over thirty such programmes in the community.

Destroyed homes in Shalyhyne community (photo on the left). Church destroyed by russians in Starykove (photo on the right)

Recovery plan. ‘Day 0’

Are you developing any scenarios for the return of your residents once the situation at the front has stabilised? What is necessary for people to be able to return to the border areas?

Firstly, the shelling must stop. However, another issue is that people will only return when there is somewhere to return to. Unfortunately, some villages are no longer habitable – they have been reduced to piles of rubble.

Does this mean that state programmes for housing reconstruction are needed?

Yes, if the state supports those who decide to live on the border, clears the area and restores the most basic infrastructure, such as the water supply, roads, medical services and education, people will live here. However, I am aware that when peace comes, the rear infrastructure will be restored first, not the border areas. The state will probably not reach us anytime soon. Perhaps this is right, because the economy must be restored first, followed by all other areas of life.

It is clear that you are determined to fight and will not back down in the face of difficulties. How do you see the future of your community?

The main guarantee that our community will never become a desert is our extremely fertile soil. In fact, it is perhaps the most fertile in all of Ukraine. This is why around 15 per cent of our land is still cultivated. Such land will certainly not remain empty; it is our future. However, the big question is whether it will be cultivated by agricultural holdings that require almost no local workers or by local farmers. This issue lies within the remit of state policy. We therefore need constant attention from the government. If farmers come to our land, their farm workers will come with them. Then there will be life!

Have you tried to preserve the local identity of the community by evacuating people to a single location where they can live together?

We did just that. This place is located in Sumy region, but I will not name it. The important thing is that they are nearby. When the time comes, these people will definitely return home. The people here are very special! Even those who lost their homes and received certificates under the eVidnovlennya programme are buying houses or flats nearby. I can at least say for sure that most of them are staying in Sumy region.

Until 2014, you were probably implementing cross-border cooperation programmes together with the russians. What can you say now about your former partners? Did they make an impact?

Indeed, we cooperated quite closely with the russians at the local level. Many people had relatives living on the other side of the border. There are quite a number of Ukrainian villages there, so people travelled there to visit their relatives. Relatives from russia also used to visit us all the time. What I can tell you is that they had been preparing for war long before 2014. Until that year, we regularly held inter-state tourist gatherings with the russians. They would come to us, and we would go to them. From their side, men aged forty or even fifty would always go to these gatherings, whereas from our side it was mostly young people. I was always surprised by this and could not understand why. Once, my russian colleague, who came to visit us on the day of the settlement, admitted that he would never be able to gather as many people as we did for a holiday. There simply were not that many people left there. That was russia’s state policy. Village councils were enlarged and people were resettled, so over time almost no one was left on the border. This situation is very convenient for an advancing army. We have the opposite situation: to defend the border effectively, it must be populated.

Tags:

16 February 2026

«Гранти – не манна небесна»: як прикордонна...

Коропська громада, що на Чернігівщині, розташована в зоні підвищеної небезпеки через близькість до кордону з рф. Тут...

16 February 2026

Вебінар «Досвід ЄС у підготовці...

25 лютого 2026 року о 11:00–13:40 шведсько-українська Програма Polaris «Підтримка багаторівневого врядування...

13 February 2026

Територіальні громади 2025: ключові зміни та їхні наслідки

Територіальні громади 2025: ключові зміни та...

Пропонуємо увазі читачів «Децентралізації» ґрунтовний аналітичний матеріал, підготовлений експертами KSE Institute —...

13 February 2026

Language of Development: Narrative Glossary of Key Terms of EU Cohesion Policy

Language of Development: Narrative Glossary of...

The European Union has its own “language of development.” It is the language used to write strategies, allocate...